National Geographic Explorer sailed overnight from the Weddell Sea, through the Active and Antarctic Sounds, to the west side of the peninsula. Our aim was to sail into Charcot Bay and, in its deepest recess, Lindblad Cove. Named after the founder of Lindblad Expeditions, the cove is sheltered and surrounded by high ice cliffs formed by the glaciers of the Antarctic Peninsula. The steep, dark mountain sides of the peninsula are home to young ice – heavy snowfalls to the west mean that the steep mountain sides slough off snow and ice at a relatively young age. Consequently, the glaciers are heavily crevassed, and we see much less rock here than on the east side of the peninsula.

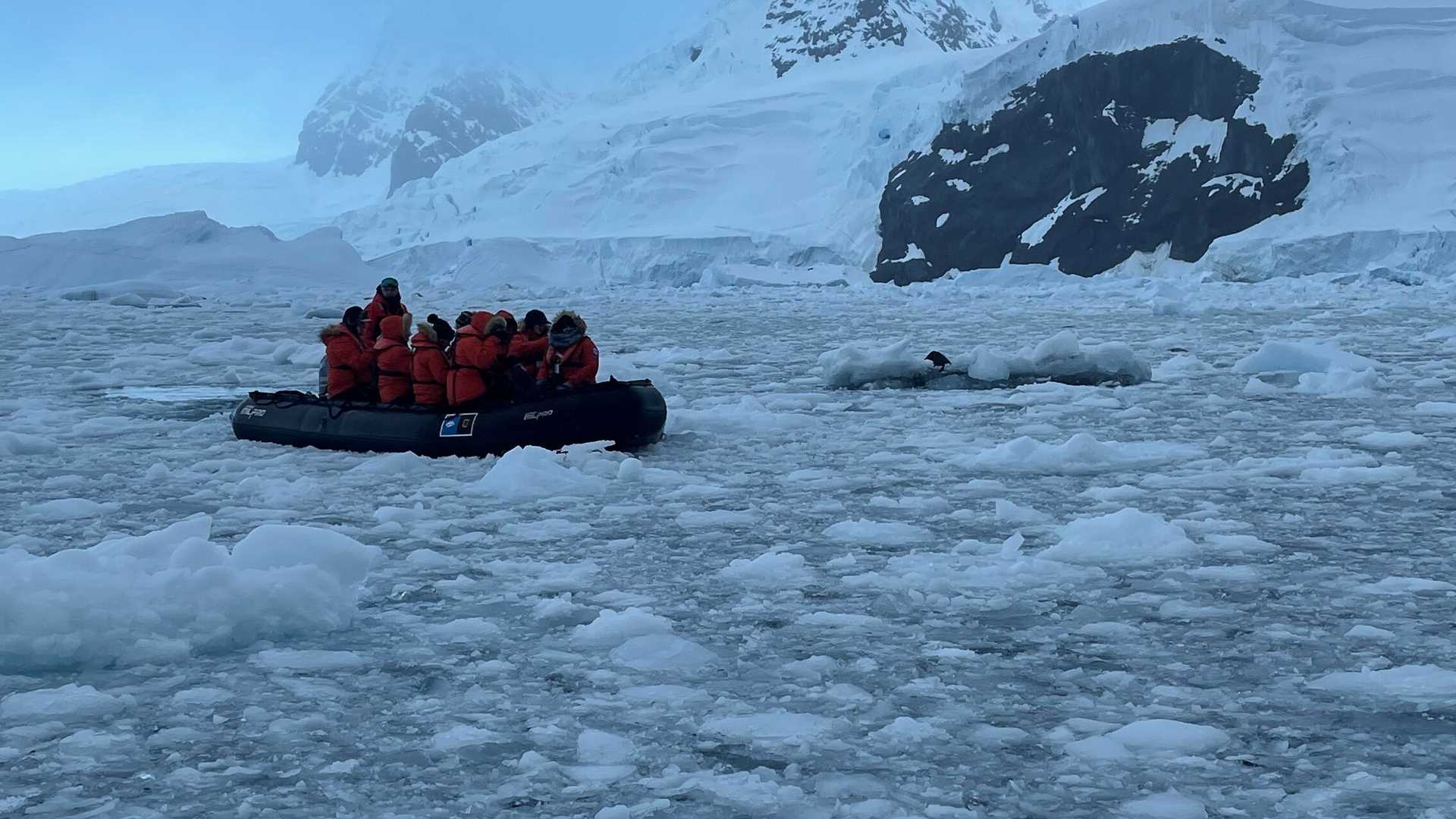

Despite heavy rain, masses of sea ice, and a long, languorous swell, we set off in Zodiacs to explore the ice. The silence of the cove was incredible. We sat for a long time and just listened, being present with our own fragility and the magnificence of all this beauty. The silence was, to use an apt phrase, deafening.

Snow petrels passed overhead, their wings silent, while a kelp gull announced her presence, coming over to the Zodiacs to check us out as she called plaintively. Through rain drenched hats and splattered goggles, smiling faces told me that there are people on board who are clearly up for all kinds of conditions. We are Lindblad, right?

A smiling band of hardy Vikings aboard a Zodiac offered hot chocolate and the odd snifter of whiskey to our soggy but delighted guests. Back on board the vessel, gloves and hats were wrung out and set aside to dry. We settled down to a lovely lunch and beautiful scenery as we sailed into low clouds. As we sailed southwest into the Gerlache Strait, the cloud base gradually lifted, and the sun began to catch the mountainsides around us. The illuminated snow was shining so brightly that it was necessary to wear our sunglasses inside the ship.

In the afternoon, Michelle La Rue, our visiting speaker, gave an excellent lecture about her work with Weddell seals and how she has used citizen scientists around the world to count the seals. Her work found that there are very few Weddell seals in the Amundsen Sea; historical literature has overestimated the seal population. The population seems to be concentrated in the Ross Sea, home to 42% of the total number of seals counted, around 200,000 in total. The early estimated population size was over 800,000. Also, interestingly, she realized that Weddell seals did not like to associate with Adelie penguins at all – and that this was consistent around Antarctica. On the other hand, they are happy associating with emperor penguins, although not too many. Michelle has given us a great insight into the work currently going on around Antarctica by her and her colleagues, and she has shared her time, passion, and energy with us.